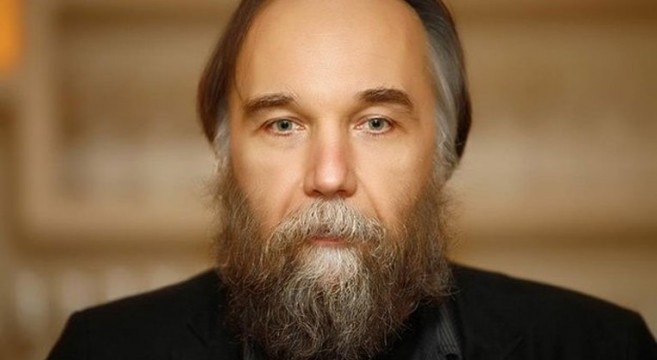

By Alexander Dugin

Translated from the Spanish by Lucian Tudor

The Anti-Americanism typical of the “Russian structure” is a continuation of the intellectual of the Slavophiles. These latter thought that one cannot fully assume Russian identity more than by getting rid of the footprint of the West, liberating oneself of this European [i.e., Western-European] manner of viewing oneself which became the norm after Peter the Great. But Europe today is no longer the Europe of the epoch of the Slavophiles, nor of the first Eurasianists. Europe is distinct from the West, that is, from the sphere of influence of the United States. Becoming Russian, today, is to liberate oneself at all levels from Western and American influence. Westernism is not solely an intellectual position, but simultaneously a contagious disease and a betrayal of the fatherland. It is for that reason that we must restlessly fight the West. In fighting against the West, the Russians affirm themselves as Russians, belonging to Russian culture, to Russian history, to Russian values.

Samuel Huntington described in a realistic manner the obstacles which inevitably face the supporters of a Unipolar World and the fanatics of the End of History. When the last formal enemy of the United States, the Soviet Union, disappeared, some imagined that the West had reached the conclusion of its liberal-democratic development and that it was going to access the “earthly paradise” of the techno-mercantile society. That was the idea of Francis Fukuyama when he wrote his famous piece about the End of History. Huntington had the merit of showing all that which contradicted the optimism then professed in the medias of globalist communication. Analyzing these phenomena, he arrived at the conclusion that they could be included under a single denomination: civilizations. This is the key word.

But that word also means the reappearance of a premodern concept in a postmodern form. The Islamic civilization, for example, existed before modernity. But in the modern epoch, colonization and secularism delegitimized the use of this term; now only Muslim “ethnic groups” were recognized. After decolonization, nation-states appeared which had a “Muslim population,” but it is only with the Iranian Revolution (where we find some traits characteristic of Traditionalism and of the Conservative Revolution) when the emergence of a Muslim state properly speaking was seen, where Islam was politically recognized as the source of power and law. Theorizing about the transition from State to Civilization, Huntington formulated a new political-scientific concept, named to thus implicitly take (and draw attention to) a new dimension of international politics which was born after the demise of the USSR. Following that, the Atlanticist milieus discovered that they would face an enemy which, unlike the Soviet Union, is not based on an explicitly formalized ideology, but which nonetheless has begun to question and undermine the foundations of the liberal and Americano-centric “New World Order.” The enemy is now the civilizations, and no longer only countries or states – a turning point.

Among all civilizations, only the Western civilization has presented itself as universal, pretending to be in this way “the civilization” (singular). In formal terms, now nobody replicates it, rather in reality the great majority of men and women who live outside of the European or American space reject this dominion, and continue to be rooted in different historical-cultural types. This is what explains the current resurgence of civilizations. Huntington concluded, concerning that, that the planetary dominion of the West will face new challenges. He advised being conscious of this danger, to prepare oneself for the reappearance of certain premodern forms in the postmodern era, and to try to protect oneself against them to guarantee the security of Western civilization.

Fukuyama was a globalist optimist. Huntington is a globalist pessimist, who analyzed the risks and measured the dangers. We can draw out a Eurasianist lesson from his analysis. Huntington was right when he said that civilizations will reappear, but he was wrong to be upset by it. In contrast, we should rejoice about the resurgence of civilizations. We should applaud it and support it, preparing the catalysts of this process and not passively observing it.

The clashes between civilizations are almost inevitable, but our task must consist of reorienting the hostility, which will not stop growing, against the United States and Western Civilization, instead of against neighboring civilizations. We must organize the common front of civilizations against one civilization which pretends to be the civilization in singular. This prioritary common enemy is globalism and the United States, which is now its principal vector. The more the peoples of the Earth will be convinced of that, the more the confrontations between non-Western civilizations can be reduced. If there must be a “clash” of civilizations, it has to be a clash between the West and the “rest of the world.” And Eurasianism is the political formula which suits this “rest.”

There is another point which, obviously, we cannot follow Huntington on: when he calls for the strengthening of transatlantic relations between Europe and the United States. The new generation of European leaders has already responded positively to this call – something which we may lament. The destiny of Europe is not on the other side of the Atlantic. Europe must clearly establish itself as a distinct civilization, free and independent. It has to be a European Europe, not American and Atlanticist. It must construct itself as a postmodern democratic empire, through the reclaiming of its cultural and sacred roots, as a part of its future as well as something residing in its past. A Europe which does not also rise up against the United States would betray its roots at the same time that it would condemn itself to not having a future. Europe also does not belong to the Eurasian space. Certainly, it can and should even be Eurasianist to the extent it adheres to this “universal idea that there is no universal civilization,” but it does not have to integrate itself into the geographic space of Eurasia. What Russians desire most is simply that Europe be itself, that is, European. Eurasianism does not consist of imposing its identity on others, but rather to help all the different identities to affirm themselves, to organically develop themselves, and to prosper. The Russian philosopher Konstantin Leontiev said that we must always defend the “flourishing multiplicity.” This is the preferred motto of the Eurasianists.

Translated from: “Huntington, Fukuyama y el Eurasismo,” Página Transversal, 6 January 2015.